The Social Dilemma is a great piece of storytelling. I’d even go as far as it being a masterpiece of docu-drama. It brings to life some complex and challenging topics in a way that the average netizen can relate to. It was compelling in focus and immersive in narrative. While it’s easy to criticise the lack of nuance in the topics it covers, these films need to create caricatures of the problems. They need to skip over the detail at times and make generalisations. Going into the details makes storytelling very challenging. Especially when wanting to connect with a general audience. In that sense, I applaud the director Jeff Orlowski, and writers Davis Coombe and Vickie Curtis for doing a fantastic job bringing this to life. So I’ll point out now that some of the areas I will cover in this post are not a direct criticism of the film. I’ve dabbled in documentaries and storytelling around complex topics. It is hard to do them justice in such a medium. But, let’s move on…

In this post I want to constructively criticise some of the ideas communicated by people featured in the film.

I will explore this through a systems thinking lens, by considering specific leverage points within these systems. These are properties of a system that, when modified, lead to flow on effects and changes in system behaviour. Donella Meadows, a renowned systems thinker, proposed that there are 12 leverage points to intervene in a system. I won’t go into all of them in this post, but will look at 6 that are relevant.

These are:

- Structure of information flows

- Rules of the systems

- Self-organising system structure

- Goals of the system

- Paradigms the systems arise from. And;

- Power to transcend paradigms

Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move the world.

Archimedes

Structure of information flow

This one is very relevant to the themes in the film. But not the one that is gonna move the world. This is all about who has access to what information and how this information is structured.

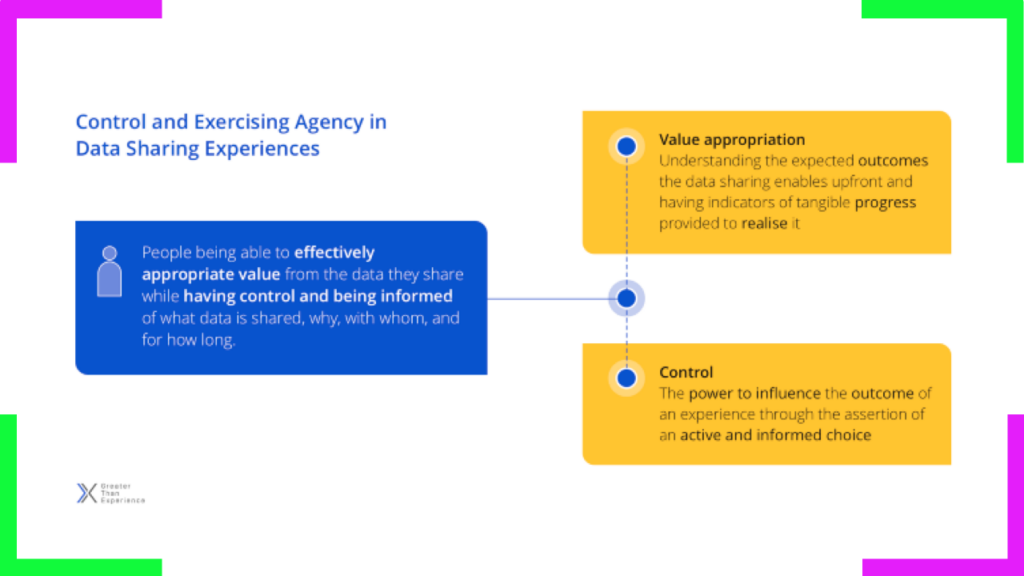

From data to information. Then to knowledge, actionable insight and power. The structure and direction of this flow can lead to information asymmetries and power imbalances. Think about it like this. We go into a business negotiation, all things equal with our human abilities. Difference is I have more information about you than you have about me. I can use this to my advantage. This is present in interpersonal relationships through to the social, political and economic systems we’ve created as a species. Micro, meso and macro scale. We can see it in stock market manipulation through to information warfare between nations states. We see it in the social media platforms with their “users” and customers.

In The Social Dilemma this asymmetry and power imbalance is illustrated well.

Three characters pulling levers and twisting the dials to manipulate Benji (the male teenage character). They know his triggers and weaknesses. His history, present context and future desires. The algorithms will win, almost always.

So change the structure and flows here to be more in balance and we change the system. Machines are a formidable foe, they don’t forget and they ruthlessly optimise for goals 24/7. They don’t factor in whether the goals hurt humans unless a human programs it to. Even then there are issues. We’ll leave algorithmic bias and ethical design for another post. And yeah, we could all connect our brains to Elon Musk’s computer, but again, who has the power there?

We can also build tools to enable people as netizens to know more about the companies and organisations they are, or intending to interact with. But for the most part, we are already overloaded with information. Proxies for trust and reputation are fundamentally broken. Social proof is becoming ineffective. Epistemic deference to “experts” is hard in a world where armchair experts reign and credentials are difficult to verify. Large news media organisations have made this worse. As was core to themes in the film, we are more divided and polarised than we have ever been in modern history. From broadcast and narrowcast to algorithmic curated reality bubbles. The threads that bind the social fabric are fraying. The scale and velocity of technological change is impossible for our slow evolving brain and nervous system to keep up with. This is not the lever to lift the world. But it is still important to factor in.

Rules of the system

This is tricky and I’ll dive into a bit more detail on this one. Mainly because it’s touted and shouted as the pathway by many advocates of ‘progressive change’. But be aware of the rules and who makes them. Systemic corruption and cronyism is pervasive. Regulatory capture is real and our rules and regulations form the programming language and scripts of our “social contract”.

Advocated for by many of the talking heads in this film is regulating big tech.

Regulations mean companies have the spectre of punishment to contend with. The stick seems to be mightier than the carrot in our current paradigm. Or at the least, a go to mechanism to address “market failures”.

These seem on the surface to be logical solutions. Ensure companies are protecting people’s personal data. Have rules to make sure there are effective security measures in place to mitigate risks of things like data breaches. Algorithmic bias audits. It goes on. Data rights, personal data use licenses and taxes. Regulations beget lobbyists and we have seen how that turns out.

I agree that rules of a system are powerful leverage points. Things like (dis)incentives and constraints influence human decision making and thus system behaviour. This may change behaviours of the powerful tech FANG or GANDALF (insert whatever acronym is relevant) and and a suite of others. But regulating and taxing companies is a stopgap. It will lead to some marginal gains in the short term but is likely to create and exacerbate problems in the medium to longer term. If we last that long as hairless apes given the interconnected crises we face.

I am not saying we need no laws and regulations. We need rules. But when it comes to regulating big tech, most approaches are far from effective. Be that data, consumer and environmental protection or antitrust laws. Institutions like the Information Commissioners Office in the UK are utter failures if we are to be honest. Most others are no different. A little like the Hague punishing some war criminals but not others.

The bigger companies seem to be circumventing this wherever they can. This example from facebook goes to a root problem where consent as a legal construct is seen to fix things. Under GDPR consent is only one of six lawful basis for processing and in the facebook case they changed their Terms and Conditions to rely upon ‘contract’ as opposed to consent to collect and process peoples information. Sneaky evasion, or just smart gaming of the system in the current paradigm. Maybe a matter of perspective.

Data protection laws will evolve to be more focused on data use contracts between consumers and companies. The technology for this is emerging. This is where tokenised access to data is cryptographically bound to explicit terms and parameters codified in the tokens. Data is handled in the client (app) with very little if any personal data sent to the server. Some call this the API-of-me or Me2B. But this is a while off before adoption takes place to catalyse meaningful change. The architecture of the web is also not suited for this and many of the business models that have dominated the web are so reliant on a surveillance capitalism. But for the purposes here, let’s go with this ‘data use contracts’ thread.

In this case, use arrangements need to be accounted for and enforcement must be more efficient. Blockchain this and that. Might seem like it has legs.

This aligns to what the advocates of personal data property rights are pushing for. It was even a ‘unique selling point’ in Andrew Yang’s failed presidential election campaign. A UBI based on harvesting our digital selves to support data driven innovation. Lots of challenges with this but let’s cover one, the conundrum of spillover effects. I’ll use an example to elaborate.

I post an image of me and some friends from an event we attended to a social media platform. Facial recognition algorithms and possibly meta data from the image are used to profile me and people I know. This feeds into a stream of experiments to test hypotheses in predicting my behaviour (and that of people in the picture). The friends in the image had no control over this. In the current paradigm, there is little transparency to what the social media platform is explicitly doing. While I may have made an active and appropriately (mis)informed choice, my control over use is limited.

I’ll add another layer.

Let’s say the image was taken at an event by a professional photographer. I bought the photo from her website and then shared it. The original copyright may have been transferred to me through the purchase. This aspect is clear. But if the photographer shared it on her social media page/profile I had no control over this. Consent may have been inferred from attending the event. Or let’s say this is in Europe. It’s covered under GDPR and the intent to post the event pictures up on numerous websites and social media platforms is hidden away in some terms. Contract is used as the lawful basis for processing. The terms had non-exclusive rights over use covered. I’ll put aside the behavioural phenomenon and systemic problem of how we bypass online agreements like terms and conditions and that of data protection law for now.

How might this work in terms of property rights?

The difficulty can first be seen in determining the point at which the relation to me and others in the image is sufficient to establish property rights. Then in the traceability of such relation. A messy area currently both socio-technically and legally. This may well be solved in the future, though I am not confident it will.

Tokenised data, DIDs and smart contracts using blockchain technologies are being proposed as technical solutions to these problems. But in the case of the photographer taking the photo these solutions in my view tend to break down. (Maybe privacy preserving tech is part of the firmware on the DSLR camera? Able to immediately identify data subjects where unambiguous and informed consent was provided. Transferred securely via the event operators infrastructure to the photographers camera). It is messy and complex. Like most of life.

Just as individuals have been accustomed to ticking the boxes to get to that e-commerce purchase on a shiny new gadget, so will be compliance for most organisations. After all, it’s just a cost burden on a business. It will also create issues for smaller businesses with complicated rules to comply with. Some companies might use the regulations as an opportunity to innovate and create shared value with their customers—even explore alternative business models like data and platform cooperatives. For companies with a culture doing true human-centred design and responsible innovation that practice things like privacy-by-design and privacy engineering this might be seen as a natural transition. But, these organisations are few and far between.

Many organisations will comply and those that don’t will fund the growth of the bureaucratic state. Smaller businesses could end up so overburdened by the compliance costs in that they end up insolvent. Many will be acquired. Gobbled up by companies that have managed to maintain compliance, not get caught out, or more likely, had their lobbyists and cronies achieve their goals.

Should the rules based lever be the priority. Well, there is a whole burgeoning industry called RegTech that is set to be the hero of that story. Compliance-by-Design with the sweet sauce of regulatory capture the dish of the day.

There is a quote in the film that stuck out. It is from a 20th century thinker that has been an inspiration for me for almost two decades. Also, the quote was powerfully pertinent in the context of the film.

Whether it is to be utopia or oblivion will be a touch-and-go relay race right up to the final moment.

Buckminster Fuller

More relevant to what I’ve just covered is another quote from Bucky.

…we have inspectors of inspectors and people making instruments for inspectors to inspect inspectors.

Buckminster Fuller

Big-Tech breeds Reg-Tech. And more subversive is the undermining of process with lobbyists.

Tread with caution down the pathway of more rules and regulations. Fit for purpose regs are sometimes like a mirage as who pays the piper calls the tune.

I’ll stop here and say that we should still be exploring some of these approaches. Jumping forward with elaborate and difficult to enforce regulations does have its pitfalls. But if pursued, it’s best done in multi-stakeholder, transdisciplinary learning environments where the legal, social, ethical and technical considerations can be mapped and experimented with. Both in lab type settings and in the field. Even better through networks of living labs and wholistic sandbox style environments. Learn by doing.

Let’s move to the next lever and fulcrum…

Self-organising systems structure

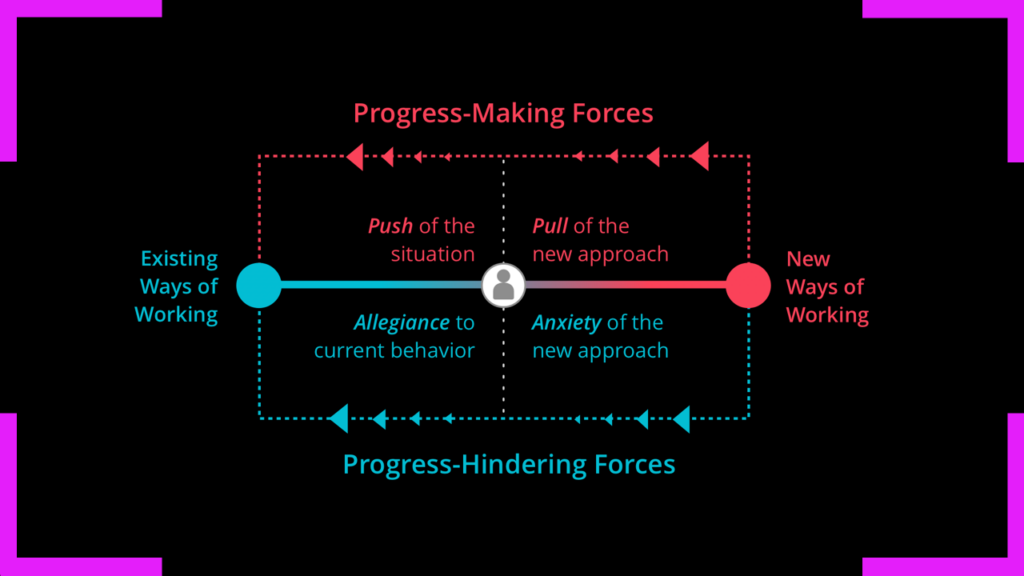

We are an amazingly adaptive and resilient species. When strong forces, shocks and crises are present we usually figure it out. This is another system leverage point. In this approach people as designers, engineers, data scientists etc need autonomy to make decisions. Cross functional teams in businesses need this to self-organise. Citizens and communities need self determination to do this. But organisational structures and behaviours need to match. The paternal and authoritarian leadership styles, patterns of civil engagement and tokenistic approaches of democracy that currently dominate are a major hindrance. This is baggage from the industrial revolution. It might have served a purpose then but it makes this scenario challenging while this paradigm still reigns supreme.

Add to this the massive industry built to enforce the paternal approach. Lawyers, policy think-tanks, auditors and consultants. Thousands upon thousands of inspectors all lining up to exert power. A burgeoning industry exists here. One that is full of people wanting to maintain relevance and exercise their authority and expertise. Hold the power they have. They have a lot to lose in systems change. But they all have value to contribute. So it is not about throwing the baby out with the bathwater. This is a good leverage point for systems intervention and one I have been focusing on my work. Supporting individuals and teams on the journey in closing the ethical intent to action gap. Learning by doing, together. Involving many tiny steps to designing more trustworthy products and services to that contribute to mutually assured thriving. A worthwhile goal to be aiming for.

Importantly, self organising tends to really kick into place when there are shocks to the system. A crisis or technological innovation released we need to rapidly adapt to. Like what is likely to happening in the realm of artificial intelligence. The ideas, mental models and patterns that are prevalent at the time dictate what self organising takes place.

Goals of the system

All systems have a purpose. Our nested internal biological systems as humans have many. Maintaining homeostasis might be one for example. Together the primary goal might be to stay healthy long enough to reproduce and nurture the next generation. A healthcare system might be made up of many sub-systems, all with inter-related goals. Our economies, political systems and technological systems all have a purpose. They change in definition over time but this is the lever. And a very powerful lever is to change the goals of a system. This changes many other properties of the system by virtue of its function. Forget the whole connecting people to Elon Musk’s super computer via Neuralink. We can ease off the regulatory accelerator and avoid creating more inspectors to inspect the inspectors ad infinitum.

This is one of the things that stuck out to me early on in the film. The reference to what defines success. An algorithm is optimising for it. Running multivariate experiments to find the most effective path to achieve it. Companies focus on it. At some point in the chain we as humans define it. Be it engagement, growth, revenue or any other metric that “matters”. Time well spent, wellbeing determinants or shifting perceptions and behaviour. What we measure influences what we value. It shapes how we behave. Especially in the current paradigm. Even more so for those responsible for designing products and services used by millions or billions of people.

This get’s at a critical issue missed in the film. Possibly because it brings up even more complex areas of the social dilemma we are in as a species.

We are optimising for the wrong things.

Debates on shareholder primacy have raged for sometime. Milton Freidman articulated it in New York Times Magazine on September 13, 1970, in an article titled “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits”. This has dominated corporate governance and the laws that regulate it. Most countries will have a law for this. One where the obligations of directors is to maximise shareholder value.

There are arguments to say we need to shift away from this paradigm. There is a revival of calls for companies to benefit stakeholders. This includes stakeholders as customers, employees, the environment and in some cases the broader communities in which companies operate. This is referred to as Stakeholderism. An “ism” used more in academic circles, particularly in business law, management and governance.

The overwhelming focus on maximising shareholder value leads to externalities. Its a cold rationalisation that can have dire consequences. This might be facebook’s impact on democratic elections. Or the addiction and dopamine depletion through the use of smart-ass phone apps. Events in recent history also illustrate this. Think of the Union Carbide Bhopal disaster where over half a million people were exposed to tons of the deadly methyl isocyanate gas. Or toxic waste being dumped into rivers in Papua New Guinea by Australian multinational BHP with the OK-TEDI mine. Impacting the livelihood of thousands, destroying species habitat that will likely never recover. There are soo many similar instances. All the laws and corporate social responsibility have not done much to stop this. Teams of lawyers, PR and backdoor deals mean legal rules are a blunt stick to deal with these systems problems.

But maybe changing the goals of these systems will help. This might mean changing a few lines in laws where the responsibilities of directors are defined. The U.S business roundtable in August 2019 declared it’s time for companies to consider the value delivered to shareholders. Klaus Schwab, the founder of the World Economic Forum, jumped on the bandwagon. Proclaiming that we need businesses to “fully embrace stakeholder capitalism.” Now, the theme of the 2020 Davos conference is the #GreatReset, “Stakeholders for a Cohesive and Sustainable World.” I maintain a healthy dose of skepticism that this is going to be more than PR. But I’ll give the benefit of the doubt here. Particularly when calls are being made for more participatory approaches to defining what all this means and what courses of action to take. I have to regularly remind myself that sociopaths and narcissists are not representative of everyone in the echelons of power.

In saying this, I’d argue we need to ensure there is skin in the game for decision makers. In both the public and private sectors.

The outcomes that matter to stakeholders can be tied to remuneration of corporate executives. This may well shift behaviour. Again, incentives matter.

The same is needed in the public sector. Yes the economy is important. But GDP and unemployment figures are poor measures of our success and that of our elects. They may have worked for rebuilding societies after the 20th century wars but it’s time for renewed focused on the metrics that matter. Politicians should have their remuneration structure redesigned. Their position in office should be connected to performance on improving metrics like the wellbeing of the citizenry. From national scale down to that of a local government or council. This gives them, skin in the game.

New Zealand designing its entire budget based on wellbeing priorities is a progressive move. One all countries should be seriously considering.

We can change the goals of the systems and collectively define them. They are not immovable like the laws of thermodynamics. We can intentionally design them and the changes influence most other properties of the system. Things can, and will self organise as a result. Rules will change. But if the incentives don’t match, the feedback loop delays might take too long. The frog in the water analogy is apt. Skin in the game is needed.

Paradigms the system arises from

There are unstated assumptions we have. There are collections of beliefs that we hold and stories we tell. The stated and unstated values we hold, the mental models we use to sense make and interact in a complex world. These all influence the perception of ourselves and our role in the world. The time we have is limited. As individual beings and, over long enough time horizons, as a species on spaceship earth. Money can be made. Economies rebuilt and restructured. Technologies rearchitected. Software refactored. Communities created and loved ones saved. The narratives we’ve shaped and can create are powerful in catalysing unity, a sense of shared humanity and directing our focus and energy.

The problems well illustrated in The Social Dilemma have arisen from our current narratives. This is changing. The very fact this film was made and many people that talked as “insiders” is a signal of this shift. All accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic and a convergence of other issues. Many are rethinking the world we live in and the responsibility we have to future generations and other lifeforms on this planet.

A paradigm shift is underway. The conveyer belt stopped, partly thanks to a virus (probabilistic origins yet to fully be established if ever) and people realised that the rat race was nothing more than that of our own creation. We can, and must, do better.

Power to transcend paradigms

This is one that really moves mountains. A lever that lifts the world.

We are capable of transcending the current paradigm and developing new ways of learning, thinking, doing, relating and being. We can choose to define what we truly value and measure that. Instead of it being the other way around. We can reconnect with ourselves, each other and nature, realise that we are part of it, not separate from it. This, on the surface, seems like an incompatible belief set coming from the western enlightenment ideas that have shaped our current paradigm. Ones that inspired us to do great things. Inventing technologies and systems that have improved billions of people’s lives. Escaping a state of nature Hobbes referred to as “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short”. And on the flip-side, these paradigms wrought havoc and left a trail of destruction future generations will have to cleanup.

The double edged sword of our creations is always one of tension liberation or enslavement. But with our moral imagination collectively cultivated our vision should be nothing less than beautifully ambitious. So enough is enough. It’s time to begin #MakingBetterTogether.

If you’re up for pursuing a beautifully ambitious vision like this, reach out to m3.