I’ve spent a good few years trying to embed data ethics in peoples everyday workflows. Back when I started focusing on this over a decade ago it was hard to even have a conversation on data ethics. Particularly when working in startups with all the pressure and perceived constraints. The move fast and break things mentality. The pressure of operating in an environment of uncertainty with perverse incentives not aligned to doing what people believe is good and right. The dogged searching for product market fit and a scalable business model. In the client work I’ve done over the years with tech companies and enterprises, these forces and more are present.

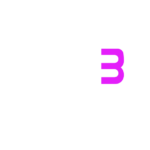

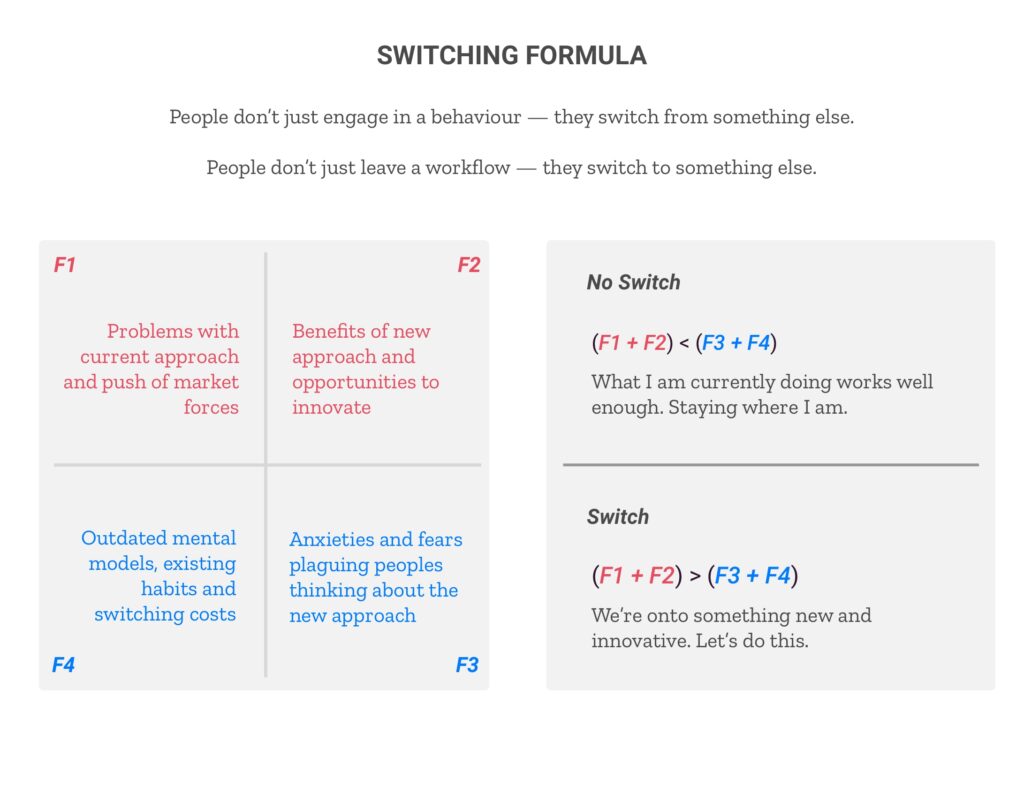

In this series I will look at how to go about operationalising data ethics. Making it real and moving beyond principles and Governance frameworks that sound brilliant but fail to bring about culture change. The first part in this series explores some insights I’ve gained over the past several years. It’s all contextualised using a framework called the Switching Canvas. Narrowing in on forces that represent the status quo and the desired new behaviours needed for operationalisation to stick.

In this series will aim cover:

- Data ethics and why it’s important

- What the Switching Canvas is and where it originated

- The behavioural forces in relation to operationalising data ethics

- Approaches to using the switching canvas in your work

- Views on how to go about operationalising data ethics in an organisation

- A system for ethical decision making that interfaces with modern product development workflows

Part one will cover:

- The switching canvas and some short origin story

- Data ethics and data, information and knowledge and power in our society

- The existing behaviours that are present in relation to operationalising data ethics, and;

- The new behaviours that need to be the focus of operationalisation efforts

Ok, let’s get into it…

The switching canvas

A few years ago I was working in a product and growth role at an Australian cryptocurrency exchange. I’d been doing some thinking on behaviour change. In this industry I was in it was very relevant. Getting people to switch from where they currently invested their capital. Through to getting people to switch from using hosted wallets to managing their own keys and crypto.

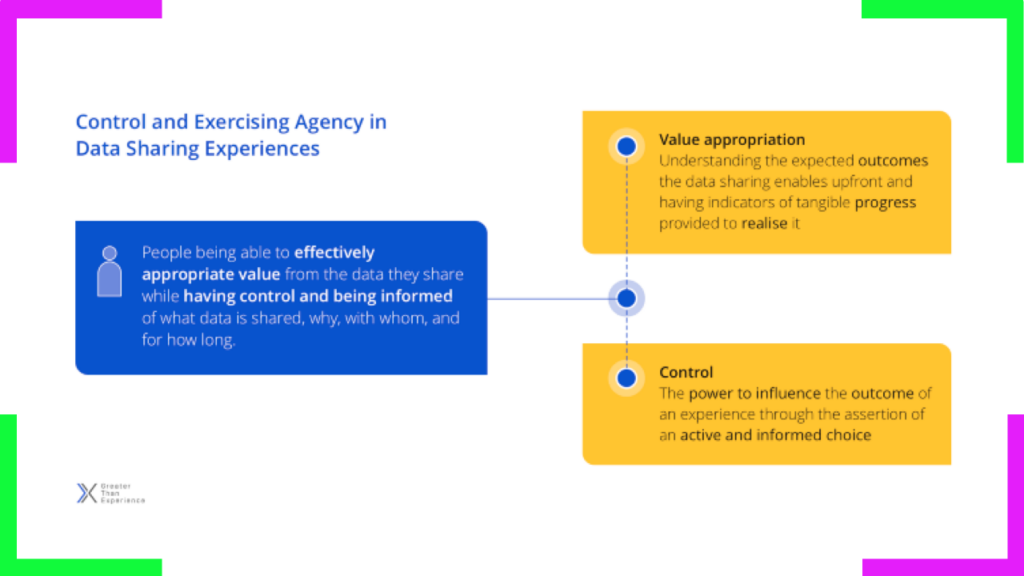

At the time I was working to contribute to the work of the talented Nathan Kinch on Data Trust by Design in the background. A set of principles, patterns and practices to help organisations design more trustworthy data enabled products and services. Those foundations we laid in late 2017. Approaches typically applied in the context of data sharing experiences. Nathan had released the first playbook and in this was a model I was familiar with called the switching formula. I took the switching formula and spent some time figuring out how it was relevant to understanding the forces of change. Macro and micro. How to get people to switch from X to Y…A product, a service, a mindset, a behaviour or set of them.

This is a model informed by several areas in the fields of social and behavioural psychology. Like what forces influenced migration patterns of migrants. To looking at the forces influencing an individual to switch a banking provider. I’d also incorporated in my understanding of behaviour design. Influenced by the work of BJ Fogg in his foundational work at the Stanford Persuasive Technology Lab (now called the Behaviour Design Lab).

More recently Nathan Kinch and I used the switching canvas in work to understand the forces change in organisations. To help on the transformation journey. To move from high level feel good ethical principles, to actual behaviours that catalyse change. Tiny changes that compound over time.

It was core to the work I led on the CX guidelines for the Consumer Data Right. Informing the CX Workstream on Consent Management and Revocation. It’s a useful tool.

For the purposes of this article I won’t cover the theoretical elements of the switching formula in much detail. I’ll be exploring the switching canvas as a tool in the context of use. To understand the forces of change when operationalising data ethics. To embed ethical decision making in the everyday workflows of cross functional product teams. Enabling the creation of more socially preferable products and services.

So let’s get stuck into it.

Operationalising data ethics

Data Ethics is an emerging field of study. It focuses on evaluating moral dilemmas. The ones related to how information is used in order to help develop morally ‘good’ solutions. It’s broad in scope. Encompassing everything from direct data collection and use in consumer to business interactions. To the unintended consequences of algorithmic bias in machine learning models.

Here’s a definition from the Royal Society.

Data Ethics:

evaluates moral problems related to data (including generation, recording, curation, processing, dissemination, sharing and use), algorithms (including artificial intelligence, artificial agents, machine learning and robots) and corresponding practices (including responsible innovation, programming, hacking and professional codes), in order to formulate and support morally good solutions (e.g. right conducts or right values).

Luciano Floridi and Mariarosaria Taddeo

As you can see there is a lot to unpack here. I will keep this on track. I promise.

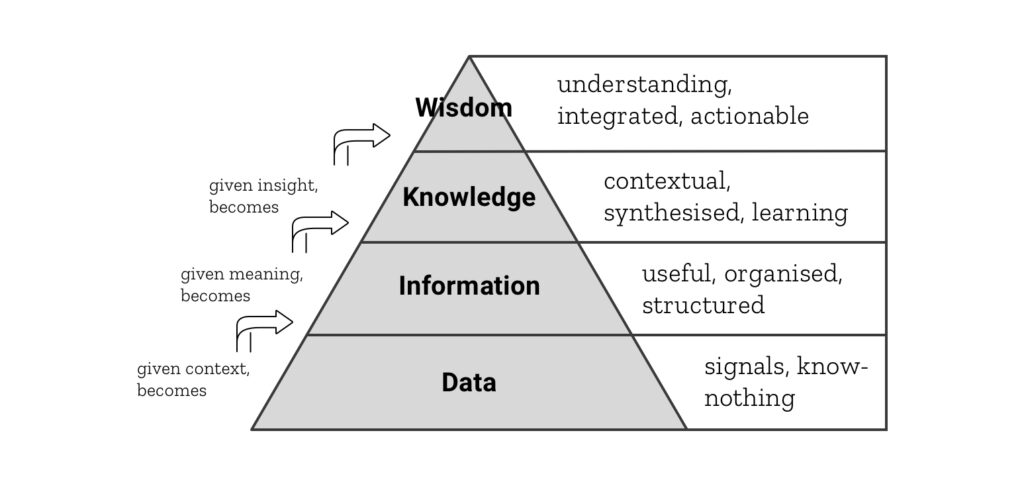

Let me first clarify some distinctions between data, information, knowledge and wisdom. I’ll use the well established DIKW Pyramid.

So in the case of data ethics, in contrast to information ethics, it is dealing with the lower level. Those small morsels of data. Shifting enquiry, from being information-centric to being data-centric.

Ok now let’s get back on track. We’re talking about operationalising data ethics and switching behaviours here.

First I want to just touch on the why. Most of you reading this know why we should be doing this. But it’s worth reinforcing.

Put simply, because it matters. Though there is more to it than that.

Our modern world is in part, powered by data. This data is about us humans and our social lives. At some point flows from us. As originators of the data or via the sensors, algorithms, standards and infrastructure we collectively create.

The past few decades, particularly since the web and digital products and services became ubiquitous the pace of data generation is growing exponentially. There is lot’s of stats thrown around on this in the order of many terabytes per second. Its hard to fathom. But we’ve been distracted. Collecting it because we can. Building products that collect swathes of it without even a reason why. Ok, back to the DKIW pyramid and some context. I’ll add a extra aspect here. Power.

Controlling the infrastructure of data and information flows and the generation of knowledge is power. Having knowledge at your fingertips is power. Having the ability to use data, information and knowledge to improve your live, finances, health etc. This is power.

In our current world the power distribution is uneven. But let’s look at some origins and context of DKIW.

In 1974 American educator Nicholas L. Henry coined the term knowledge management. He distinguished data from information and information from knowledge. This built on work from the economist and educator Kenneth Boulding. He presented a hierarchy consisting of signals, messages, information, and knowledge. Data is not valuable without the means of turning it into information. Then that information into knowledge and having the power to take action on this. This has all been facilitated by a broad category of information and communication technologies. In the past this was story telling and the spoken word, ancient hieroglyphs and the printing press. Now it’s digital databases. Ones and zeros. Programming languages and things like micro transistors that make modern computers. Radio spectrum management and television. Satellites and the physical infrastructure of the internet. Networks of wires, cables and computers. The technologies of the modern web. The sciences of communication, symbols, semiotics and semantics.

Data is worthless without all of this. Without the ability to transform data into actionable insights. To catalyse machine and human action. For the betterment of people and the ecological systems we all rely upon for life. This ability to generate, extract and derive value from data comes with consequences both positive and negative. Some intended, some not. And with this power comes responsibility.

We’ve seen this power used for political and economic gain through targeted information warfare. The disempowering of populations. The targeting of minorities and usurping of political and legal due process. It been used to hook people to products. Emulating them on a server to experiment on as their digital twin. Making them addicts of the infinitely scrollable feed, to the detriment of their very wellbeing. It is at the basis of social cooling. Where pervasive surveillance influences the diversity of thinking, being and doing. Where we are polarised and trapped in our timeline echo chambers. An emerging existential threat constraining our ability as a species to adapt to a complex and chaotic world.

On the flip side we’ve got so much to be grateful for with all this technological advancement.

It’s helped us to diagnose children with potentially life threatening illnesses before they are born. Then have machine learning augment the prognosis and treatment. It’s helped us to preempt natural disasters and social conflict. Or to allocate resources to minimise the negative impact on human life. It’s helped long lost siblings and loved ones reunite. It’s been at the foundations of catalysing positive social change. It’s powerful.

Those little digital stories we generate on an almost continual basis have been used to shape us. In ways we usually don’t realise. Used more often than not to restrict our agency. But also to support us as people in exercising it. This is the duality of our life and the tech we create. The creation of technology and how data is used does not happen in a social vacuum. It represents our biases, vices and fears. Our hopes, aspirations and our dreams. Dark mirrors and bright. All colours of the rainbow. In this sense how it’s used in the systems to organise it’s all designed matters.

Ethical design and use of technology is prominent in many global discussions. How we use data, particularly the data that represents people is going through a paradigm shift. Data protection regulations have emerged. Ethical by design frameworks and tools to help organisations in complying and innovating.

Who controls the flow of information can lead to power imbalance in our societies. Like wealth distribution, knowledge is unevenly distributed. The insight that comes from it that when contextualised transform into wisdom.

The time is now, to take stead and learn from the past. Because we can intentionally design the future in which we can thrive.

Ok, that’s out of the way but let’s get back to it…

Operationalising data ethics is about moving from current Ways of Working (WoW) to the new WoW. A question of how might we bring the ethical decision making process into the everyday workflows of people in their work contexts. Specifically those working with data and designing for it’s collection and use. Data scientists. Product designers. UX designers. Service designers. Marketers. Data protection and privacy peeps. Business analysts, machine learning engineers, software developers and more. Those cross functional teams working on data enabled products and services.

So switching from old to new. Making ethical enquiry into data collection and use part of the way people think, learn, explore, design and make. Creating value for people and planet.

I’ll keep this focused on commercial entities as best as possible. Public sector entities have some similar but also different challenges.

So now let’s look at some of the existing behavioural themes.

From old to new

In any change work there are existing behaviours that represent the status quo. Then the desired behaviours that represent to new reality. This is part of the switch. Getting an understanding of current state and defining the new state. A new modus operandi.

Let’s now look at some of the prevailing behaviours that represent the current reality. Then the ones needed to realise the transformation. First with existing behaviours and then the desired ones.

Existing behaviours

These are the existing behaviours people in organisations are trying to move away from.

Lack of depth

There’s an evident lack of depth in the thinking on issues related to data ethics. The tooling and mental models to effectively assess the collection and use of data. Assessing it in alignment to the purpose, values and principles of the organisation. Designing products and services using data about people, from humans like you and me. Due diligence on a new software vendors and where it might compromise the stated ethical position of an organisation.

It’s an afterthought

Data ethics was (and still is) seen as an afterthought and people are more often reactive rather than proactive in approaches. It’s put on the back-burner, underfunded or not resourced at all. Wilful ignorance is pervasive. The ostrich effect playing out – “we know this is a problem but would prefer to ignore it and maybe deal with it later” type of mindset.

Wilful ignorance

People in cross functional teams responsible for designing and engineering are erring on the side of caution. They are not forcing the discussion when a concern comes up. In some cases this might have been because of a lack of psychological safety. In other cases it is not the modus operandi to raise this “type of thing”.

Inconsistent practices

Despite regulations like GDPR, ethical data practices lack consistency across the organisation. People within a design team for instance might treat customer data with more respect than marketing. And engineering teams might be oblivious to the ethical concerns when it comes to the collection and use of customer data. A lack of cohesion in the practices and teams across the business. Many are still working in silos. Cross functional collaboration is still piecemeal.

Low priority

Operationalising data ethics is still seen as a low priority. Where budget flows priorities go. Thus, the authorising environment is lacking. Initiatives to operationalise rarely translate into the trenches. There might be some board discussions. A blog post from the CEO or even a new hire. Chief Trust & Safety Officer or something like that. Sometimes there is budget allocated to operationalisation efforts. In my experience working in this area, budgets get pulled. Capital redirected from an area deemed as less of a “priority”. This is a transformation exercise were are talking about here. Old ways of thinking, learning, relating, perceiving value, creating and interacting must transform. Whole of organisation change. Bottom up and top down. Because the reality is that most organisations are still pyramids. Not circles. Where capital flows signal priorities. This is unacceptable. If companies or public sector institutions want to show they are trustworthy and create positive change in the world. Fund it.

Over reliance on legal

Then comes the over reliance on legal personnel to deal with data ethics issues. This might be data protection practitioners or even general legal counsel. This was something I’ve seen time and time again. They tend to have some philosophical skills from training in jurisprudence. But they should never be the sole arbiter of ethical dilemmas when it comes to data collection and use. I’ll touch more on this when it comes to new behaviours.

These could be unpacked further but this is a blog post, not a book. So let’s now give the new, desired behaviours a look.

New behaviours

These are the behaviours deemed to bring about the transformation. The ones needed to embed ethical decision making in the everyday workflows of people in the business. They can be mirrors to the old behaviours representing a shift to the new. So let’s cover a few.

The authorising environment

There’s a need to have everyone engaging in the transformation efforts. This is for any initiative required to operationalise data ethics. People in senior leadership and management (SLAM) need to embrace the ambiguity that comes with this type of work. We see the phrase “ethics is everyone’s job” popping up more and more. But if the authorising environment is not there and board and leadership support is absent, nothing much will change. And that change is more than just some principles, a blog post from the CEO and some (usually piecemeal) funding. It needs to be an organisation wide commitment. That starts with the ones responsible for setting strategy and identifying and mitigating against downside risk. The board and executive committee.

Toolkits and validation

Harnessing and validating existing tools to support ethical decision making is part of the work. This might be upfront in product discovery, during feature development or in retrospect and review. The tools might be basic ones to augment thinking or rigorous ones that need loads of time, effort and collaboration. Finding the right ones for the task at hand is part of the journey and like any tool people need to learn how, when and why to use them.

Psychological safety

For any of this transformation to take place people in teams need real psychological safety to have the hard conversations. Being able to flag an issue and escalate it to resolution. This is such a crucial part. If it’s missing most efforts will fall flat and fail.So there needs to be courageous action at scale – modelling the behaviour at the bottom and the top.

Stakeholder involvement

Bringing in diverse groups of people into the process matters. Building bodies of evidence to support ongoing decision making about what you “should” do. This is positive friction. It slows the process but means you can account for lot’s of perspectives. Minimising the likelihood of some new feature or product negatively impacting people’s lives. This is everything from cross functional teams, customers, and even regulators and civil society. This might be in a distinct codesign process or through activities like community juries, or social preferability experiments.

Continual learning

Learning is never done. Nor is ethics. When operationalising data ethics in an organisation a focus on continual learning is needed. This might be about the emergent technologies and their ethical use. Or learning new ways of perceiving, of moving beyond compliance mindsets. Building new bodies of empirical evidence, and establishing common ground. Having a way for teams to engage in collective pattern recognition. Reflect, stress test and continually exercise that “ethical muscle memory”. It’s about learning more of the nuances to data ethics. About knowledge building and ongoing social learning.

Curiosity and humility

It’s all too common that these initiatives to operationalise data ethics get bogged down in seriousness. It should be taken seriously but should also be approached with curiosity and humility. Acknowledging the limited depth of understanding about the ethical issues with data. Being open, curious and humble. This creates a more playful approach. It enhances motivation and collaboration and brings people together. Driving innovation not compliance.

Wrapping up

As you’ll likely recognise there are sets of behaviours that matter to any operationalisation efforts. They reflect the current Ways of Working and desired future behaviours we can all work towards. Being mindful of our fallibility and failing forward as people striving to use data for good. I see the positive momentum in this interdisciplinary field of tech ethics. It’s inspiring, but much more needs to be done to close the ethical intent to action gap.

At some point I’ll take this further in part 2 and cover the progress making and progress hindering forces. The forces of change that need to be amplified or countered if efforts to operationalise data ethics are to be successful.

These are all discussions we all need to have as practitioners. As communities and as people. Because how we reflect, learn, interact and create matters.

We actively use the switching formula and canvas approach in our work at Tethix.

You can download a PDF copy of the canvas here. We’re working to creative commons license and open source the toolkit at some point in the future.

Reach out if you want to collaborate, chat or dive deeper into the how.